Prevention of Medical Errors for Florida Healthcare Professionals

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

FLORIDA NURSES MANDATORY COURSE. This Prevention of Medical Errors CEU fulfills the 2-hour requirement for Florida nurses and other select initial licenses and renewals. Covers causes of medical errors, common errors and how to prevent them, root cause analysis, and Florida's medical error reporting requirements. 24-hour reporting to CE Broker for existing license holders. See approved licenses for this mandatory course.

"I always purchase your course on medical errors for FL health professionals. I really like the fact I can see the materials before I take my test and pay for it—and that I can also look at it again in the future." - Yu, RN in Florida

"The way material was presented made it easy to understand." - Diahann, LPN in Florida

"I like the updated info since the last time I took this course." - Teresa, RN in Florida

"I really appreciate that the information has been updated and is accurate. Thank You!" - Emily, RN in Florida

Prevention of Medical Errors for Florida Healthcare Professionals

Copyright © 2024 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this course, you will understand current, evidence-based error reduction and patient safety measures to prevent medical errors in the practice setting. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Define “medical errors” and associated terminology.

- Describe the most common medical errors and strategies to prevent them.

- Identify institutional strategies to reduce medical errors.

- Discuss Florida’s statutory requirements for addressing medical errors.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare providers know medical errors create a serious public health problem that poses a substantial threat to patient safety. Yet, despite providers’ best efforts, medical error rates remain high, with significant disability and death. Errors can occur at any point while an individual is in the healthcare system—in hospitals, clinics, surgery centers, dialysis centers, medical offices, dental offices, nursing homes, pharmacies, and even in patients’ homes—anywhere that patients receive healthcare services.

It is estimated that approximately 400,000 hospitalized patients experience some type of preventable harm each year, including surgical, diagnostic, medication, devices and equipment, system failures, infections, and falls. Most errors in outpatient healthcare are related to a missed or late diagnosis.

Analyzing why medical errors happen has traditionally been focused on the human factor, concentrating on individual responsibility for making an error, and the solutions have involved training or retraining, additional supervision, or even disciplinary action. Healthcare professionals experience profound psychological effects such as anger, guilt, inadequacy, depression, and suicide due to real or perceived errors. The loss of clinical confidence and fear of punishment can make healthcare professionals reluctant to report errors.

The alternative to this individual-centered approach is a system-centered approach, which assumes that humans are fallible and that systems must be designed so that humans are prevented from making errors. The trend is for patient safety experts to focus on improving the safety of healthcare systems to reduce the probability of errors and mitigate their effects rather than focus on an individual’s actions.

Errors represent an opportunity for constructive changes and improved education in healthcare delivery. Acknowledging that errors happen, learning from them, and working to prevent errors in the future are important goals and represent a major change in the culture of healthcare—a shift from blame and punishment to analysis of the root causes of errors and the creation of strategies to reduce the risk of errors. In other words, healthcare organizations must create a culture of safety that views medical errors as opportunities to improve the system. Every person on the healthcare team has a role in making healthcare safer for patients and workers (Rodziewicz et al., 2023).

DEFINING MEDICAL ERRORS

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine defined a medical error as “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended (i.e., error of execution) or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim (i.e., error of planning)” (IOM, 1999). Errors can include problems in practice, products, procedures, and systems.

Errors can be further be described as adverse events. Important subcategories of adverse events include:

- Preventable events, in which harm may have been lessened or prevented had patient safety risk mitigation strategies been applied. Example: Performing surgery on the wrong body part.

- Negligent adverse events resulting from care that falls below the standards expected of clinicians in the community. Example: Not properly monitoring a patient under anesthesia.

- Unpreventable adverse events that result from complications that cannot be prevented given the current state of knowledge. Example: Appropriately prescribing, dispensing, and administering a drug to a patient not known to have an allergy who subsequently has an allergic reaction.

- Ameliorable events, which are not entirely preventable but may have resulted in less harm if the care had been provided differently. Example: A clinician failing to respond to a patient with medication-related symptoms.

(Boisvert & Pellet, 2022; Rodziewicz et al., 2023)

In addition to adverse events, other terms used to describe medical errors include near misses, sentinel events, and serious reportable events (SREs).

Near Misses

A near miss (also known as a close call) is an incident that might have resulted in harm but did not occur because of timely intervention by healthcare providers, the patient, or the patient’s family. Example: A nurse recognizes a potential drug overdose in a physician’s prescription and does not administer the drug but instead calls the error to the physician’s attention (Performance Health Partners, 2024).

Sentinel Events

Sentinel events are those medical errors resulting in death, permanent harm, or severe temporary harm and intervention required to sustain life. Such events are called sentinel because they signal the need for immediate investigation and response (VA, 2023).

The Joint Commission adopted a formal Sentinel Event Policy in 1996 to help hospitals that experience serious adverse events improve safety and learn from the events.

Organizations benefit from self-reporting in the following ways:

- The Joint Commission can provide support and expertise during the review of a sentinel event.

- The organization can collaborate with a patient safety expert in the Joint Commission’s Sentinel Event Unit of the Office of Quality and Patient Safety.

- Reporting raises the level of transparency in the organization and promotes a culture of safety.

- Reporting conveys the organization’s message to the public that it is doing everything possible, proactively, to prevent similar patient safety events in the future.

(TJC, 2024a)

Not all sentinel events occur because of an error, and not all medical errors result in sentinel events. Examples of sentinel events include:

- Surgery or other invasive procedure performed on the wrong site or wrong patient

- Patient death or serious injury associated with a medication error

- Suicide during treatment or within 72 hours of discharge

- Death or serious injury to a neonate

- Discharge of an infant to the wrong family

- Patient death or serious injury associated with a fall in the healthcare setting

- Abduction of a patient/resident of any age while receiving care

- Sexual abuse/assault on a patient or staff member in the healthcare setting

- Criminal event

(Kamakshya & De Jesus, 2023)

Serious Reportable Events (SREs)

The National Quality Forum has compiled a list of serious reportable events, which are consequential, largely preventable, harmful adverse events (also referred to as never events, or events that should never happen). SREs are grouped into seven categories, as follows:

- Surgical SREs (e.g., surgery/invasive procedure performed on wrong body parts or the wrong patient)

- Product/device SREs (e.g., patient death/serious injury associated with use of devices, drugs, or biologics provided by the healthcare setting)

- Patient-protective SREs (e.g., patient elopement or suicide while in a healthcare setting)

- Care management SREs (e.g., patient death/serious injury associated with a fall while in a healthcare setting, medication errors)

- Environmental SREs (e.g., patient death/serious injury associated with the use of restraints while in a healthcare setting, burns, electric shock)

- Radiologic SREs (e.g., patient/staff death/serious injury associated with the introduction of a metallic object into an MRI area)

- Criminal SREs (e.g., sexual abuse/assault on a patient or staff member within or on the grounds of a healthcare setting)

(NQF, 2024)

Active and Latent Errors

Active errors (human errors) are those that occur at the point of contact between a human and some aspect of a large system (e.g., a machine). They are generally readily apparent (e.g., pushing an incorrect button or ignoring a warning light) and almost always involve someone at the front line.

Latent errors are accidents waiting to happen. They refer to a less apparent failure in system or process design, faulty installation or maintenance of equipment, or ineffective organizational structure that contributes to the occurrence of errors, allowing them to cause harm to patients (Sameera et al., 2021).

COMMON MEDICAL ERRORS AND HOW TO PREVENT THEM

Medical errors usually occur in stressful, fast-paced environments such as emergency departments, intensive care units, and operating rooms. Errors often occur when staffing is inadequate and necessary personnel are not available when needed (Carver et al., 2023).

The 10 most common causes of medical error include:

- Ineffective communication (the most common cause)

- Changes in clinician’s ability to make good judgments and quick decisions

- Deficiencies in education, training, orientation, and experience

- Inadequate methods of identifying patients, incomplete assessment on admission, failing to obtain consent, and failing to provide patient education

- Inadequate policies and procedures to guide healthcare workers

- Lack of consistency in procedures

- Inadequate staffing and/or poor supervision

- Technical failures associated with medical equipment

- No audits in the system

- No one prepared to accept responsibility or change the system

(Rodziewicz et al., 2023)

Medication Errors

Medication errors are the most common errors in both outpatient and inpatient settings. Each year in the United States, over 7 million people are affected, and 7,000 to 9,000 people die due to a medication error. In addition, many other patients experience but often do not report an adverse reaction or other complications related to medication. The total cost of caring for patients with medication-associated errors exceeds $40 billion each year (Tariq et al., 2023).

Causes of medication errors include:

- Expired product, usually related to improper storage

- Administering medication for a shorter or longer duration than prescribed

- Incorrect preparation before final administration

- Incorrect strength

- Incorrect rate, most commonly with IV push or infusions

- Incorrect timing, which may lead to under- or overdosing

- Incorrect dose, including overdose, underdose, and extra dose

- Incorrect route, often resulting in significant morbidity and mortality

- Incorrect dosage form, such as immediate release instead of extended release

- Incorrect patient action correctible only with patient education

- Known allergen

- Known contraindication

Medication errors may be due to human errors but often result from system failures, such as:

- Inaccurate order transcription

- Failure to disseminate drug knowledge

- Failing to obtain allergy history

- Incomplete order checking

- Mistakes in tracking of medication orders

- Poor professional communication

- Unavailable or inaccurate patient information

(Tariq et al., 2023)

Medication errors are most common during the ordering or prescribing stage, although errors may occur at any step in the process. Errors typically include the healthcare provider writing the wrong medication, wrong route or dose, or wrong frequency. These ordering errors account for nearly 50% of medication errors. Nurses and pharmacists identify from 30% to 70% of medication-ordering errors.

ORDERING/PRESCRIBING ERRORS

The most common errors in the ordering/prescribing step include:

- Ordering the incorrect drug

- Ordering the incorrect dose

- Ordering the wrong interval or drug schedule

- Ordering the wrong route

- Ordering the wrong dose form

- Ordering the wrong infusion rate

- Ordering while not being aware of allergies, preexisting medical conditions, or known contraindications

- Ordering without reviewing and being aware of current medications being taken

(Tariq et al., 2023)

Prevention strategies when prescribing and ordering include:

- Always preparing one prescription for each medication

- Besides signing the prescription, always circling one’s name on the preprinted prescription pad

- Double-checking the dose and frequency

- Considering that each medication has the potential for adverse reactions

- Not using drug abbreviations when writing orders

- Always adding the patient’s age and weight to each prescription

- Checking the patient for liver and renal function before ordering any medication

- Spelling out the frequency and route of dosage; not using abbreviations

- Always specifying the duration of therapy; not indicating “give out X number of pills”

- Being aware of high-risk medications

- When writing a prescription, stating the condition being treated

- Using computerized provider order entry (CPOE)

- Reconciling medication at times of care transitions

- Double-checking orders by two healthcare professionals prior to dispensing or administering

(Tariq et al., 2023; Loria, 2023)

DISPENSING ERRORS

Dispensing errors are usually judgmental or mechanical. Mechanical errors include mistakes in dispensing or preparing a prescription, such as dispensing an incorrect drug, dose, quantity, or strength. Judgment errors include:

- Failing to detect drug interactions

- Performing an inadequate drug utilization review

- Failing to appropriately screen

- Failing to appropriately counsel the patient

- Giving improper directions

- Inappropriately monitoring

Prevention strategies when dispensing include:

- Taking time to speak to the patient and double-checking their understanding of the dose, drug allergies, and any other medications they may be taking

- Ensuring the entry of the prescription is correct and complete

- Being aware of look-alike, sound-alike drugs and utilizing tall-man lettering (TML), a technique that uses uppercase lettering to highlight the differences between similar drug names by capitalizing dissimilar letters (e.g., “CISplatin” vs. “CARBOplatin”)

- Using computer alerts or stocking a single strength of the medication in the pharmacy

- Organizing work space, work environment, and workflow

- Reducing distractions whenever possible

- Focusing on reducing stress and balancing heavy workloads

- Storing drugs properly

- Always providing thorough patient counseling

(Tariq et al., 2023; ISMP, 2023)

ADMINISTRATION ERRORS

Medication errors in the administration process have been estimated to be 8% to 25% in hospitals and long-term care facilities. Intravenous administration had a higher estimated error rate, ranging from 48% to 53%. A substantial proportion of medication administration errors occur in hospitalized children, largely due to weight-based pediatric dosing. Medication errors in the home are reported to occur at rates up to 33%. Wrong dose, missing doses, and wrong medication are the most common. Factors include low health literacy and poor provider-patient communication (MacDowell et al., 2021).

Prevention strategies when administering a medication include adhering to the “five rights” of medication administration:

- Right patient

- Right drug

- Right dose

- Right route

- Right time

An additional four “rights” have been proposed. These include:

- Right documentation: entering the administration of a medication in the patient’s medical record

- Right action/reason: confirming why patients are being given a medication, and that it is an appropriate treatment for their condition

- Right form: ensuring the correct form of administration within a given route (e.g., tablet, powder, liquid, suppository, etc.)

- Right response: monitoring the person’s response to the medication and ensuring it’s having the desired effect

Another strategy that has been shown in some studies to decrease administration errors up to 50% is the use of barcode medication administration (BCMA), which allows nurses to verify the five rights of medication administration by electronically scanning a patient’s wristband to confirm the information and crossmatch with the patient’s electronic medical chart. This has been shown to decrease administration errors by 23% to 50% (Hanson & Haddad, 2023).

Other prevention strategies for prevention in inpatient settings include:

- Smart infusion pumps for intravenous administration

- Single-use medication packages

- Package design features, such as tall-man lettering for look-alike drug names

- Minimizing interruptions

Few of these interventions are likely to be successful in isolation, and efforts to improve safe medication use must also focus on transitions to home, primary care, and patient caregiver understanding and administration of medication. These efforts include:

- Patient education

- Revised medication labels to improve patient comprehension of administration instructions

- Multicompartment medication devices for patients taking multiple medications in ambulatory or long-term care settings

- Being proficient in medication calculations

- Maintaining up-to-date pharmacologic knowledge

- Informing patients of a medication’s therapeutic effects

- Documenting accurately once a medication has been administered

(AHRQ, 2021)

MONITORING ERRORS

Monitoring involves observing the patient to determine if the medication is working, is being used appropriately, and is not harming the patient. Types of errors in monitoring that can occur include:

- Failure to monitor effectiveness of therapeutic action of a medication

- Lack of awareness of side effects of a medication

- Failure to monitor, assess, and report laboratory tests

- Failure to monitor, assess, and report vital signs

- Failure to educate patients about potential side effects

- Failure to comply with a pain management program

- Communication failures during handoff procedures to accepting nurse

(Tariq et al., 2023, MacDowell et al., 2021)

ERRORS WITH HIGH-ALERT MEDICATIONS

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) defines a high-alert medication as a drug that has a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when used in error. Examples include U-500 insulin, antithrombotic agents, opioids, vasopressin, and many others.

Although errors may or may not be more common with such medications, the consequences of errors are much more devastating. The ISMP makes the following recommendations for reducing errors with high-alert medications in the acute care settings, community/ambulatory settings, and long-term care (LTC) settings, which may include:

- Standardizing the ordering, storage, preparation, and administration of these medications

- Improving access to information about these drugs

- Using auxiliary labels and automated alerts

- Employing redundancies—duplicate devices used for backup purposes to prevent or recover from the failure of a specific part of the process (e.g., asking another nurse to perform an independent check)

- Providing mandatory patient education

(ISMP, 2024)

Surgical Errors

At least 4,000 surgical errors occur in the United States each year. Surgical errors include retained foreign bodies; mislabeled surgical specimens; and wrong-site errors, wrong-procedure errors, and wrong-patient errors (WSPEs). Errors can occur at various stages in the surgical process.

Some causes of surgical errors include:

- Lack of adequate surgeon training and education

- Absence of standardized rules and regulations

- Major gap in communication between surgeon, anesthesiologist, and other ancillary staff

- Gap in communication between the surgeon and the patient

- Use of unreliable systems or protocols

- Rushing to complete cases

- Human factors

(Santos & Jones, 2023; Rodziewicz et al., 2023)

Instances of retained surgical items are known to occur approximately 40 times per week in the United States, and the most common are surgical sponges or laparotomy pads, which then become gossypibomas, or masses within the body comprised of a cotton matrix surrounded by a foreign body reaction. These gossypibomas account for 48% to 69% of retained foreign bodies (Steris Healthcare, 2024). Clamps and retractors are the most common types of retained instruments. The second most common category is catheters and drains. Needles and blades are the third most common category, a majority of which are suture needles.

Anesthesia-related adverse events are fairly uncommon, although not rare. The American Society of Anesthesiologists reports that approximately 1 in every 200,000 patients experiences an anesthesia-related complication leading to mortality. Common anesthesia errors include, but are not limited to:

- Dosage errors (overdosing and underdosing)

- Delayed delivery of anesthesia

- Improper intubation

- Improper monitoring

- Failure to respond to a patient’s vital signs

- Equipment malfunction

- Failure to complete a thorough patient history to identify allergies or drug interactions

- Poor communication

(Shaked, 2024)

Data from the Joint Commission Sentinel Event Annual Review showed there were 85 WSPEs sentinel events in the year 2022, and 65% of these errors were wrong-site surgeries.

Interprofessional collaboration is crucial for preventing surgical errors, including safety checklists, briefing and debriefing, error reporting, and effective communication. Nurses are essential in monitoring patient vital signs, administering appropriate medications and fluids, and ensuring all necessary steps are taken before and after procedures (TJC, 2023).

The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist (see box below) was developed after extensive consultation aimed at decreasing errors and adverse events, and increasing teamwork and communication in surgery. This checklist has gone on to show significant reduction in both morbidity and mortality and is now used by a majority of surgical providers around the world (WHO, 2021).

ELEMENTS OF THE WHO SURGICAL SAFETY CHECKLIST

A surgical checklist is an algorithmic listing of actions to be taken in any given clinical situation intended to make everyone aware that others expect these things to be done.

“SIGN-IN” checklist must be completed orally and in writing before induction of anesthesia (with at least a nurse and anesthetist).

- Has the patient confirmed their identity, site, procedure, and consent?

- Is the site marked?

- Is the anesthesia machine and medication check complete?

- Is the pulse oximeter on the patient and functioning?

- Does the patient have a:

- Known allergy?

- Difficult airway or aspiration risk?

- Risk of >500 mL blood loss (7 mL/kg in children)?

“TIME-OUT” checklist must be completed orally and in writing before skin incision (with nurse, anesthetist, and surgeon).

- Confirm all team members have introduced themselves by name and role.

- Confirm the patient’s name, procedure, and where the incision will be made.

- Has antibiotic prophylaxis been given within the last 60 minutes?

- For the anticipated critical event:

- To surgeon:

- What are the critical or nonroutine steps?

- How long will the case take?

- What is the anticipated blood loss?

- To anesthetist:

- Are there any patient-specific concerns?

- To nursing team:

- Has sterility (including indicator results) been confirmed?

- Are there equipment issues or any concerns?

- To surgeon:

- Is essential imaging displayed?

“SIGN-OUT” checklist must be completed orally and in writing before the patient leaves the operating room (with nurse, anesthesia provider, and surgeon).

- Nurse verbally confirms:

- The name of the procedure

- Completion of instrument, sponge, and needle counts

- Specimen labeling (read aloud labels, including patient name)

- Whether there are any equipment problems to be addressed

- To surgeon, anesthetist, and nurse:

- What are the key concerns for recovery and management of this patient?

(WHO, 2024)

Tubing Misconnections

The FDA reports that medical device misconnections can occur when one type of medical device is attached in error to another type of medical device that performs a different function. Tubing misconnections can occur for several reasons. The most common reason is that many types of tubing lines for different medical devices incorporate common Luer lock connectors, which consist of a male taper with an associated threaded “skirt” and a female taper having flanges to engage the threads (FDA, 2023).

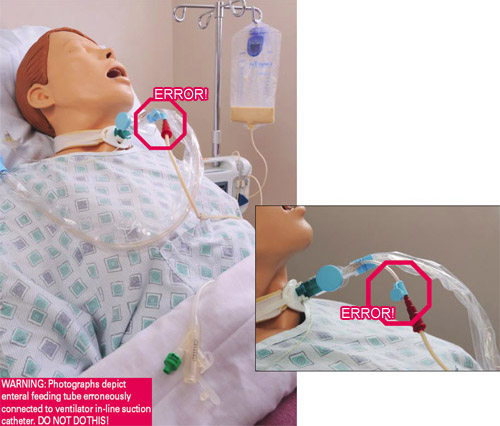

EXAMPLES OF TUBING MISCONNECTIONS

- Enteral feeding tube connected to an IV

- Enteral feeding tube connected to ventilator in-line suction catheter

- Blood pressure cuff tubing connected to an IV port

- IV tubing connected to tracheostomy cuff

- IV tubing connected to nebulizer

- Oxygen tubing connected to a needleless IV port

- IV tubing connected to nasal cannula

- Syringe connected to tracheostomy cuff

- Epidural solution connected to a peripheral or central IV catheter

- Epidural line connected to an IV infusion

- Bladder irrigation solution utilizing primary IV tubing connected to a peripheral or central IV catheter

- Foley catheter connected to NG tube

- IV infusion connected to an indwelling urinary catheter

- IV infusion connected to an enteral feeding tube

- Primary IV tube connected to a blood product meant for transfusion

(FDA, 2023)

Patient’s feeding tube is incorrectly connected to the instillation port on the ventilator in-line suction catheter, delivering tube feeding into the patient’s lungs, causing death. (Source: FDA, 2023.)

PREVENTING TUBING MISCONNECTIONS

Attempts to prevent device misconnections have included color-coding, labels, tags, and training. However, these methods alone have not effectively solved the problem, because they have not been consistently applied, nor do these methods physically prevent the misconnections.

In order to reduce the chances of tubing misconnections, non-Luer lock connections have been introduced. These include the NR-Fit connector for neuraxial and regional anesthesia catheters and the Enfit connectors for feeding tubes.

These connectors are designed to be incompatible with Luer adaptors, which are commonly used in IV applications. The connectors look and secure very similarly to a Luer threaded lock system, although the design is larger and, therefore, incompatible with connectors for unrelated delivery systems such as tracheostomy tubes, IV lines, and catheters (Rodziewicz et al., 2023).

Until new connectors are universally adopted, the following interventions offer healthcare providers with strategies such as the use of “ACT” to prevent device misconnections (see table).

| Label | Step | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| (FDA, 2023a) | ||

| A | Assess equipment |

|

| C | Communicate |

|

| T | Trace |

|

Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs)

HAIs are infections that occur while receiving healthcare in a hospital or other healthcare facility and that first appear 48 hours or more after admission or within 30 days after having received healthcare. HAIs are considered system failures and are often preventable. As many as 1 in 31 hospitalized patients and 1 in 43 nursing home residents contract at least one HAI in association with their healthcare (CDC, 2022).

HAIs AND HAND HYGIENE

One of the most important reasons in healthcare settings for the spread of bacteria resulting in HAIs, some of which are antibiotic resistant and can prove life-threatening, is the failure of physicians, nurses, and other caregivers to practice basic hand hygiene. Studies show that some healthcare providers practice hand hygiene on fewer than half the occasions they should. Providers might need to clean hands as many as 100 times per 12-hour shift, depending on the number of patients and intensity of care (CDC, 2023a).

PREVENTING CATHETER-ASSOCIATED URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS (CAUTIs)

CAUTIs occur at a rate of approximately 3% to 10% per day of catheterization, making duration of catheterization an important risk factor. Complications of CAUTIs include sepsis, bacteremia, and involvement of the upper urinary tract (Fekete, 2023).

Recommended prevention strategies include:

- Inserting catheters only for appropriate indications and leaving in place only as long as needed

- Considering other methods for bladder management such as intermittent catheterization or external male or female collection devices, when appropriate

- Using appropriate technique for catheter insertion

- Practicing hand hygiene immediately before insertion of the catheter and before and after any manipulation of the catheter site or apparatus

- Inserting catheters following aseptic technique and using sterile equipment

- Using a catheter with the smallest feasible diameter to minimize urethral damage

- Properly securing indwelling catheters after insertion to prevent movement and urethral traction

- Maintaining a sterile, continuously closed drainage system

- Replacing the catheter and collecting system using aseptic technique when breaks in aseptic technique, disconnection, or leakage occur

- When collecting a urine specimen, collecting a small sample by aspirating urine from the needleless sampling port with a sterile syringe after cleaning the port with disinfectant

- Maintaining unobstructed urine flow

- Using portable ultrasound devices for assessing urine volume to reduce unnecessary catheterizations

- Ensuring the collecting bag remains below the level of the bladder

- Not placing the bag on the floor

- Preventing kinking of the catheter and collecting tube

- Emptying the collection bag regularly using a separate collecting container for each patient, and avoiding touching the drainage spigot to the container

- Cleaning the meatal area with an antiseptic solution

(Patel et al., 2023)

PREVENTING SURGICAL SITE INFECTIONS (SSIs)

SSIs affect approximately 0.5% to 3% of patients undergoing surgery, accounting for 20% of all HAIs. SSIs are associated with up to an 11-fold increase in risk of mortality, with 75% of SSI-associated deaths directly attributable to the SSI (Seidelman et al., 2023).

The CDC recommends the following prevention measures for SSIs:

- Administering preoperative antimicrobial agents only when indicated by published clinical practice guidelines, and timing the administration so that a bactericidal concentration is established when incision is made

- Administering appropriate parenteral prophylactic antimicrobial agents before skin incision in all cesarean section procedures

- In clean and clean-contaminated procedures, not administering additional prophylactic antimicrobial agent doses after the surgical incision is closed in the OR, even in the presence of a drain

- Not applying antimicrobial agents (i.e., ointments, solutions, or powders) to the surgical incision with the aim of preventing SSI

- Considering the use of triclosan-coated sutures for prevention of SSI

- Implementing perioperative glycemic control and using blood glucose target levels lower than 200 mg/dL in patients with and without diabetes

- Maintaining perioperative normothermia

- Advising patients to shower or bathe the entire body with either antimicrobial or nonantimicrobial soap or an antiseptic agent on at least the night before the day of the procedure

- Performing intraoperative skin preparation with an alcohol-based antiseptic agent unless this is contraindicated

- Not applying microbial sealant immediately after intraoperative skin preparation, as it is not necessary for prevention of SSI

- Avoiding the use of plastic adhesive drapes with or without antimicrobial properties

- Considering intraoperative irrigation of deep or subcutaneous tissues with aqueous iodophor solution

- Not withholding transfusion of necessary blood products from surgical patients undergoing prosthetic joint arthroplasty as a means of preventing SSI

- In clean or clean-contaminated prosthetic joint arthroplasties, not administering additional antimicrobial prophylaxis doses after the surgical incision is closed in the OR, even in the presence of a drain

(Singhal, 2023)

PREVENTING CENTRAL LINE–ASSOCIATED BLOODSTREAM INFECTIONS (CLABSIs)

CLABSIs are laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infections that are not secondary to an infection at another body site and that are due to the presence of an intravascular catheter that terminates at or close to the heart, or in one of the great vessels, that is used for infusion, withdrawal of blood, or hemodynamic monitoring (NHSN, 2024).

| (Buetti et al., 2022; Kolikof et al., 2023; Srinivasan et al., 2023) | |

| Prior to insertion |

|

| During site selection |

|

| During insertion |

|

| After insertion |

|

PREVENTING PERIPHERAL IV CATHETER–RELATED BLOODSTREAM INFECTIONS

Peripheral intravenous catheters are the most commonly used invasive medical device in healthcare. They should be used for short-term IV therapies (up to 7 days), should not be used if oral treatment is available, and dwell time should be short (less than 4 days).

| (Jacob & Gaynes, 2020; Zingg et al., 2023) | |

| During site selection |

|

| During catheter selection |

|

| During insertion |

|

| During catheter and site care |

|

| Replacing administration sets |

|

PREVENTING CLOSTRIDIOIDES DIFFICILE INFECTIONS

Clostridioides (formerly known as Clostridium) difficile (C. diff) infections (CDIs) cause life-threatening diarrhea. They are usually a side effect of taking antibiotics. Those most at risk are patients, especially older adults, who take antibiotics and also receive medical care and people staying in hospitals and nursing homes for a long period of time (Cleveland Clinic, 2024).

Prevention strategies for CDIs include:

- Isolating and initiating Contact Precautions for suspected or confirmed CDI

- Maintaining Contact Precautions for at least 48 hours after diarrhea has resolved, or longer, up to the duration of hospitalization

- Adhering to recommended hand hygiene practices

- Using dedicated patient-care equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, stethoscopes)

- Implementing daily patient bathing or showering with soap and water

- When transferring patients, notifying receiving wards or facilities about the patient’s CDI status

- Performing daily cleaning of CDI patient rooms using C. difficile sporicidal agent at least once a day, including toilets

- Cleaning and disinfecting all shared equipment prior to use with another patient (e.g., wheelchair)

- Performing terminal cleaning after CDI patient transfer/discharge using a C. difficile sporicidal agent (EPA List K agent)

- Cleaning additional areas that are contaminated during transient visits by patients with suspected or confirmed CDI (e.g., radiology, emergency rooms, physical therapy) with C. difficile sporicidal agent (EPA List K agent)

- Restricting use of antibiotics with the highest risk for CDI (e.g., fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins)

- Limiting the use of nonantibiotic patient medications (e.g., proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor blockers) that are hypothesized to increase risk for CDI

- Evaluating and testing asymptomatic patients at high risk for CDI; isolating those testing positive, but not treating in the absence of symptoms

- Considering additional disinfection of CDI patient room with no-touch technologies (e.g., UV light)

- Dedicating healthcare personnel to care of patients with CDI only to minimize risk of transmission to others

- Expanding the use of environmental disinfection strategies (e.g., sporicidal agents [EPA List K agent]) for daily and terminal cleaning in all rooms on affected units

(CDC, 2021)

PREVENTING MULTIDRUG-RESISTANT ORGANISM (MDRO) INFECTIONS

Multidrug-resistant organisms are pathogens that are resistant to multiple antibiotics or antifungals. MDROs can be difficult to treat and can therefore cause serious illness or even death. Some MDROs are found and transmitted almost exclusively within healthcare settings. Several key pathogens include:

- Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE)

- Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter

- Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Candida auris

In the United States more than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur each year and more than 35,000 people die as a result (WIDHS, 2022; CDC, 2022).

Prevention measures for multidrug-resistant organism infections include:

- Following Standard Precautions during all patient encounters in all healthcare settings, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection or colonization status

- Following hand hygiene procedures

- Carefully cleaning rooms and medical equipment used for patients with an MDRO with an appropriate disinfectant

- Removing temporary medical devices as soon as possible

- Using antibiotics only when necessary

- Using enhanced barrier precaution during high-contact patient care activities

- Using Contact Precautions for all patients with MDRO infection or those identified as MDRO colonized

- Decolonizing patients with MDROs to eliminate MDRO carriage using chlorhexidine gargling, bathing, and showering, along with nasal mupirocin

(Binghui & Weijiang, 2024)

PREVENTING HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA (HAP) LUNG INFECTIONS

HAP occurs 48 hours or more after hospital admission at a rate of 5 to 10 per 1,000 hospital admissions. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a subset of HAP occurring in intensive care units that presents more than 48 to 72 hours after tracheal intubation and is thought to affect 10% to 20% of patients receiving mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours (Shebl & Gulick, 2023).

Prevention strategies for ventilator-associated pneumonias include:

- Avoiding intubation and preventing reintubation

- Using routine infection control practices and hand hygiene

- Minimizing sedation

- Maintaining and improving physical conditioning

- Elevating the head of the bed to 30 to 45 degrees

- Providing oral care with toothbrushing but without chlorhexidine

- Providing early enteral vs. parenteral nutrition

- Changing the ventilator circuit only if visibly soiled or malfunctioning (or per manufacturer’s instructions)

- Using selective oral or digestive decontamination in ICUs with low prevalence of antibiotic resistant organisms

- Utilizing endotracheal tube with subglottic secretion drainage ports for those patients expected to require greater than 48–72 hours of mechanical ventilation.

- Considering early tracheostomy

- Considering postpyloric rather than gastric feeding for patients with gastric intolerance or who are at high risk for aspiration

(SHEA, 2022)

Risk for Falls

Falls are the most common type of accidents in people 65 years of age and older, with over 30% of such individuals falling every year. In approximately one half of these cases, the falls are recurrent. These percentages increase to around 40% in individuals 85 years and older.

Approximately 10% of falls result in serious injuries, including fracture of the hip, other fractures, traumatic brain injury, or subdural hematoma. They are the major cause of hospitalization related to injury in those 65 years and older and are associated with increased mortality.

Falls in institutional settings occur more frequently and are associated with greater morbidity than falls that occur in the community. Approximately 50% of individuals in the long-term care setting fall yearly (Appeadu & Bordoni, 2023; Kiel, 2023).

Fall risk can be categorized as either intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic factors include issues that are unique to the individual and concern medical, psychological, and physical issues. Extrinsic factors generally can be changed and address environmental risks that patients encounter (Appeadu & Bordoni, 2023).

A fall-risk assessment is done on admission, and reassessment is done whenever there is a change in a patient’s condition or when a patient is being transferred to another unit. A reliable, standardized, and validated assessment scale should be used that includes a history of falls, mobility problems, use of assistive devices, medications, and mental status.

There are many fall assessment tools. The following tools have been extensively studied and recommended:

- Morse Fall Scale

- STRATIFY Scale

- Schmid Fall Risk Assessment Tool

After assessment of fall risk, collaboration with the patient and family takes place in order to develop a personalized plan that addresses each identified risk factor. Tailored prevention interventions are described in the table below.

| (Turner et al., 2022) | |

| Mobility and identification practices |

|

| Bed modification practices |

|

| Patient monitoring practices |

|

| Education practices |

|

| Patient safety practices |

|

| Restructuring strategies |

|

INSTITUTIONAL STRATEGIES FOR ADDRESSING ERRORS

Essential strategies healthcare facilities must consider in their efforts to reduce medical errors include:

- Changes in organizational culture

- Involvement of leadership

- Education of providers

- Development of patient safety committees

- Adoption of safe protocols and procedures

- Use of technology

(CDC, 2023c)

Patient Safety Culture

Patient safety culture describes the extent to which an organization’s culture supports and promotes patient safety and refers to the values, beliefs, and norms shared by practitioners and other staff throughout the organization that influence their behaviors and actions. Key features of a safety culture include:

- Strong support from organizational leadership

- Acknowledgement of the high-risk nature of an organization’s activities

- Determination to achieve consistently safe operations

- Responsibility by everyone for safety, implementing and reporting unsafe conditions

- A blame-free environment for individual reporting of errors or near misses without fear of reprimand or punishment

- Encouragement of collaboration about decision-making across all staff levels and disciplines to seek solutions to worker and patient safety problems

- Organizational commitment of resources to address safety concerns

(CDC, 2023c)

JUST CULTURE MODEL

In a just culture, adverse events are recognized as valuable opportunities to understand contributing factors and to learn from them. The principles of a just culture require a shift away from how healthcare organizations typically responded to adverse events in the past by immediately assigning blame and punishing the individual involved. This approach resulted in fear of consequences and, in turn, failure to disclose errors.

A just culture acknowledges that errors occur not only as a result of an individual’s behavioral choices but also as a result of system failures. When an adverse event occurs in a just culture, it is necessary to understand the behavioral choices of the individual as well as system factors. This approach to remedying the problem results in promoting of learning, managing behavioral choices, and designing safe systems to prevent recurrence.

When using the just culture model, people recognize that when they report errors, fair treatment will be received (Murray et al., 2023).

Addressing Staffing Concerns

Since 2020, nearly 1 in 5 healthcare workers have quit their jobs, and research indicates that up to 47% of healthcare workers plan to leave their positions by 2025. When an experienced healthcare professional departs the field, their knowledge goes with them. Collective knowledge loss can be damaging to both providers and patients by lowering the average experience level of hospital employees. When inexperienced personnel are trained by less-experienced staff, the knowledge deficit deepens.

With fewer healthcare personnel, the risk for medical error increases. Overworked and understaffed medical teams may make more avoidable mistakes when cognitive failure is high. Cognitive failure can be a result of stress, lack of expertise, and a heavy patient load, among other factors. When cognitive failure is high, healthcare workers may be more likely to find shortcuts to safety procedures, insufficiently monitor patients following a procedure, or suffer injuries themselves from physical hazards.

Studies have demonstrated the association between staffing ratios and patient safety, documenting an increased risk of adverse events, morbidity, and mortality as staffing ratios decreases.

Nurses play a critically important role in ensuring patient safety while providing care directly to them. Nurses are a constant presence at the bedside and regularly interact with physicians, pharmacists, families, and all other members of the healthcare team. They are crucial to timely coordination and communication of a patient’s condition to the team.

In regards to safety, a nurse’s role includes monitoring patients for clinical deterioration, detecting errors and near misses, and understanding care processes and weaknesses inherent in some systems. Nurses communicate changes in a patient’s condition and perform countless other tasks to ensure patients receive high-quality care.

Determination of adequate nurse staffing is a complex process that changes on a shift-by-shift basis, requiring close coordination between management and nursing, and is based on:

- Patient acuity and turnover

- Availability of support staff and skill mix

- Settings of care

The high-risk nature of the work, stress caused by increased workload and interruptions, and the risk of burnout due to involvement in errors or exposure to disruptive behavior, likely combined with unsafe conditions precipitated by low nurse-to-patient ratios, result in an increased risk of adverse events (Phillips et al., 2021).

Organizations need to be creative in meeting the needs of nurses with an environment that motivates and empowers their autonomy in staffing ratio decisions that consider high volume and acuity levels that will lead to less burnout and desire to exit the workforce (Haddad et al., 2023).

Leadership

Leadership is essential for the achievement of goals related to quality care and patient safety. Safety leadership in healthcare must be encouraged at all levels in an organization, from the bedside to the executive office. Inefficient, invisible leadership is a significant cause of adverse patient outcomes.

Effective leadership is necessary for communication, teamwork, situation awareness, workload management, error management, decision-making, and human performance, all of which determine quality of care. Open communication between professionals, regardless of their occupation, is also critical for the safety of patient care (Murray & Cope, 2021).

Leaders in healthcare have many responsibilities, including:

- Instilling a culture of safety

- Assessing, reducing, mitigating, and managing safety risk in a caring environment

- Maintaining a safe patient allocation based on the acuity and skill mix of the clinicians

- Evaluating team performances

- Sharing and educating patient safety measures

- Managing risky behaviors among staff

Healthcare leaders have a direct impact on the climate based on their commitment to a culture of safety that includes:

- Communication

- Fostering teamwork

- Productivity

- Scheduling

- Recognition of clinicians’ achievements that support patient safety

- Promoting a learning culture

Orientation, regular in-service training programs, and unit-specific competency training should be offered to empower clinicians to assess their own learning needs and practice safely (Haskins & Roets, 2022).

FLORIDA STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS

The 2023 Florida Statutes require every licensed facility to establish an internal risk management program and develop and implement an incident reporting system. It is the duty of all healthcare providers and all agents and employees to report adverse incidents to the risk manager or their designee within 3 business days after their occurrence.

Internal Risk Management Program Requirement

The Florida Statutes require every facility licensed under F.S. 395-1097 to establish an internal risk management program that must include the following:

- The investigation and analysis of the frequency and causes of adverse incidents

- The development of appropriate measures to minimize risk, including:

- Education and training of all nonphysician personnel as part of initial orientation and at least one hour of such education and training annually for all personnel working in clinical areas and providing patient care, except for licensed healthcare practitioners who are required to complete continuing education coursework pursuant to chapter 456 or their respective practice act

- The analysis of patient grievances related to patient care

- A system for informing a patient or designee pursuant to state law that the patient was the subject of an adverse event

- Prohibition against a single staff person attending patients in recovery rooms unless there is live observation, electronic observation, or any other reasonable measure to ensure patient protection and privacy

- Prohibition against any unlicensed person from assisting or participating in any surgical procedure unless authorized to do so

- An incident reporting system to report adverse incidents to the risk manager or designee within three business days after their occurrence

Adverse Incident Reporting Requirements

F.S. 395-0197 mandates internal reporting within three business days of any adverse incident (event) over which healthcare personnel could exercise control and that is associated in whole or in part with medical intervention rather than the condition for which such intervention occurred. These include:

- Adverse events resulting in one of the following injuries:

- Death

- Brain or spinal damage

- Permanent disfigurement

- Fracture or dislocation of bones or joints

- Limitation of neurologic, physical, or sensory function which continues after discharge from the facility

- Any condition that required specialized medical attention or surgical intervention resulting from nonemergency medical intervention, other than an emergency medical condition, to which the patient has not given his or her informed consent

- Any condition that required the transfer of the patient, within or outside the facility, to a unit providing a more acute level of care due to the adverse incident rather than the patient’s condition prior to the adverse incident

- The performance of a surgical procedure on the wrong patient, a wrong surgical procedure, a wrong-site surgical procedure, or a surgical procedure otherwise unrelated to the patient’s diagnosis or medical condition

- Surgical repair of damage resulting to a patient from a planned surgical procedure, where the damage was not a recognized specific risk, as disclosed to the patient and documented through the informed-consent process

- A procedure required to remove unplanned foreign objects remaining from a surgical procedure

Licensed facilities in Florida are required to submit two types of reports to the Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA):

- An adverse incident report must be submitted to the AHCA by mail or by using the online Adverse Incident Reporting System (AIRS) within 15 calendar days after the adverse incident’s occurrence, whether occurring in the licensed facility or arising from healthcare prior to admission to the licensed facility.

- An annual report summarizing the incident reports that have been filed in the facility for that year, including:

- The total number of adverse incidents

- Types of adverse events listed by category, and number of incidents occurring within each category

- Code numbers of each professional and individual directly involved and number of incidents each has been directly involved in

- Description of all malpractice claims filed against the facility, including number of pending and closed claims and the status and disposition of each claim

(Florida Legislature, 2024)

CONCLUSION

Everyone has a stake in the safety of the healthcare system—healthcare workers as well as the general public. In the past, patient safety was not a traditional part of the education of most healthcare workers, but today this is no longer true. All healthcare workers are being actively educated about their roles in the prevention of avoidable negative outcomes for all patients. It is essential that all clinicians understand the journey every patient makes through the system, recognize how the system can fail, and take action to prevent those failures.

To counter errors and safeguard patients, changes must continue to be made in how the workforce is deployed; in how work processes are designed; and in the leadership, management, and culture of healthcare organizations. Because communication issues are so commonly involved in medical errors, it is crucial that physicians, nurses, therapists, and other healthcare personnel work together as a team, respecting each other’s contributions to the well-being of the patients in their care. Collaborative teamwork is essential for optimizing quality and safety in healthcare.

RESOURCES

AGS Beers Criteria (American Geriatrics Society)

Florida Agency for Health Care Administration, Division of Health Quality Assurance

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

List of high-alert medications (Institute for Safe Medication Practices)

REFERENCES

NOTE: Complete URLs for references retrieved from online sources are provided in the PDF of this course.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov

Appeadu M & Bordoni B. (2023). Falls and falls prevention in older adults. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Binghui J & Weijiang Y. (2024). Prevention and control of hospital-acquired infections with multidrug-resistant organism: A review. Medicine, 103(4), e37018.

Boisvert S & Pellett J. (2022). Patient safety in dentistry: Managing adverse events in the practice setting. https://www.thedoctors.com

Buetti N, Marschal J, Drees M, et al. (2022). Strategies to prevent central line-associated bloodstream infection in acute-care hospitals: 2022 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 43(5), 553–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2022.87

Carver N, Gupta V, & Hipskind. (2023). Three ways to prevent medical errors. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023a). Show me the science. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023c). Safety culture in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Multi-drug-resistant organisms (MDROs). https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021). Strategies to prevent Clostridium difficile infection in acute care facilities. https://www.cdc.gov

Cleveland Clinic. (2024). C. diff (Clostridioides difficile) infection. https://my.clevelandclinic.org

Fekete T. (2023). Catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Florida Legislature. (2024). The 2023 Florida statues (including special session C). Chapter 395: Hospital licensing and regulation, internal risk management program. http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0300-0399/0395/Sections/0395.0197.html

Haddad L, Annamarju P, & Toneye-Butler T. (2023). Nursing shortage. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Hanson A & Haddad L. (2023). Nursing rights of medication administration. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Haskins HEM & Roets L. (2022). Nurse leadership: Sustaining a culture of safety. Health SA Gesondheid, 27, a2009. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v27i0.2009

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (1999). To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academies Press.

Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). (2024). High-alert medications in acute care settings. https://www.ismp.org

Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). (2023). Look-alike drug names with recommended tall man (mixed case) letters. https://www.ismp.org

Jacob J & Gaynes R. (2020). Intravascular catheter-related infection: Prevention. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Kamakshya P & De Jesus O. (2023). Sentinel event. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Kiel D. (2023). Falls in older persons: risk factors and patient evaluation. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Kolikof K, Peterson L, & Baker A. (2023). Central venous catheter. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Loria K. (2023). Technology trends to prevent prescription errors. https://www.drugtopics.com

MacDowell P, Cabri A, & Davis M. (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov

Murray S, Clifford J, Larson S, et al. (2023). Implementing just culture to improve patient safety. Military Medicine, 188(7–8), 1596–9.

Murray M & Cope V. (2021). Leadership: Patient safety depends on it! Collegian, 28(6), 604–9.

National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). (2024). Bloodstream infection event (central line-associated bloodstream infection and non-central line associated bloodstream infection). https://www.cdc.gov

National Quality Forum (NQF). (2024). List of SREs. https://www.qualityforum.org

Patel P, Advani S, Kofman A, et al. (2023). Strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections in acute care hospitals: 2022 update. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 44, 1209–31.

Performance Health Partners. (2024). How to avoid near miss events in healthcare. https://www.performancehealthus.com

Phillips J, Malliaris A, & Bakerjian D. (2021). Nursing and patient safety. https://psnet.ahrq.gov

Rodziewicz T, Houseman B, & Hipskind J. (2023). Medical error reduction and prevention. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Sameera V, Bindra A, & Rath G. (2021). Human errors and their prevention in healthcare. J. Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol, 37(3), 328–35.

Santos G & Jones M. (2023). Prevention of surgical errors. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Seidelman J, Mantyh C, & Anderson D. (2023). Surgical site infection prevention. JAMA, 329(3), 244–52.

Shaked P. (2024). Most common anesthesia errors and complications. https://prosperlaw.com

Shebl E & Gulick P. (2023). Nosocomial pneumonia. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Singhal H. (2023). What are the CDC guidelines for prevention of surgical site infection (SSI)? Medscape. https://www.medscape.com

Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). (2022). New guidance released for preventing hospital-acquired pneumonia. https://shea-online.org

Srinivasan A, Naidu V, & Dhivya P. (2023). Arterial line placement using modified Seldinger technique: A novel approach. Indian J Crit Care Med, 27(7), 515–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Steris Healthcare. (2024). What are retained surgical items? https://www.steris.com

Tariq R, Vashisht R, Sinha A, & Scherbak Y. (2023). Medication dispensing errors and prevention. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

The Joint Commission (TJC). (2024a). Sentinel event policy and procedures. https://www.jointcommission.org

The Joint Commission (TJC). (2023). Sentinel event data 2022 annual review. https://www.jointcommission.org

Turner K, Staggs V, Potter C, et al. (2022). Fall prevention practices and implementation strategies: Examining consistency across hospital units. J Patient Saf, 18(1), e236–42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). (2023). Glossary of patient safety terms. https://www.patientsafety.va.gov

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2023). Examples of medical device misconnections. https://www.fda.gov

Wisconsin Department of Health Services (WIDHS). (2022). Multi-drug-resistant organisms (MDROs). https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov

World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). Patient safety. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Global patient safety action plan 2021–2030. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032705

Zingg W, Barton A, Bitmead J, et al. (2023). Best practice in the use of peripheral venous catheters: A scoping review and expert consensus. Infect Prev Pract, 5(2), 100271.

Customer Rating

4.2 / 1342 ratings